Today we’re joined by Vijay Raina, a leading specialist in enterprise SaaS technology and software architecture. He’s here to unpack a novel approach to AI-powered application development that’s gaining traction in the enterprise world. As businesses rush to leverage AI, many are hitting a wall with skyrocketing costs, code that’s difficult to maintain, and a frustrating gap between design vision and final implementation. We’ll explore how an intermediate, markup-first strategy can address these critical challenges, focusing on cost control through reduced AI token consumption, the importance of generating maintainable code for long-lived applications, and fostering seamless collaboration between designers and developers.

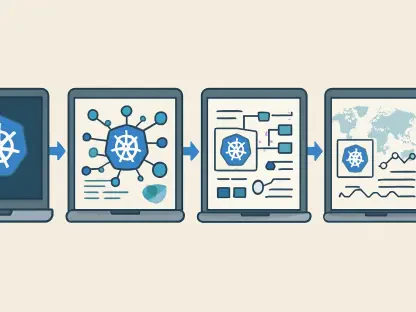

Your platform uses a “two-pass model” that generates a tech-agnostic markup from a Figma file before producing code. Could you walk through that process and explain how this intermediate step helps developers verify the application’s direction early on?

Absolutely. The core idea is to bridge the chasm that so often exists between user experience design and the actual implementation. Instead of going straight from a design intent to a massive block of code, which can be a real black box, we introduce a crucial intermediate step. A team submits their Figma design files and describes their intent in natural language. Our system then performs a first pass, generating a lightweight, tech-agnostic application markup. This isn’t raw code; it’s a structured representation of the application. This gives developers a tangible, early checkpoint to verify that the AI is on the right track before any heavy lifting happens. It essentially brings the design canvas directly into the development workflow, collapsing that gap and ensuring everyone is aligned from the start.

Enterprise teams often face soaring AI token costs when generating code. How does your markup-first approach specifically reduce LLM token consumption, and can you share any examples of the potential cost savings compared to direct-to-code generation methods?

This is a problem we’re seeing everywhere, and it’s hitting enterprise budgets hard. When you ask a large language model like Claude or Gemini to generate entire applications, the token consumption for the output can be astronomical. Our approach directly counters this. By first generating a lightweight intermediate markup, the actual load on the LLM is kept very, very low. We’re asking the model to do a much simpler, more focused task. Then, a deterministic engine takes that verified markup and performs the final code generation. Because this second pass isn’t relying on a costly, token-based LLM, we are not consuming nearly as many tokens as a direct-to-code method would. This architecture is a direct response to seeing those bills soar; it’s designed from the ground up to be economically sustainable for large-scale enterprise use.

Enterprise apps must be maintained and evolved for years. How does generating “real code” from an intermediate markup help teams add features and fix vulnerabilities over time, and what specific steps does it take to prevent the kind of design drift that plagues long-lived applications?

This is the reality of enterprise software—it’s never a one-and-done project. All the applications built on our system are long-lived applications, and they need to be adaptable for years to come. That’s why it’s critical that what you get at the end is real code, not something locked in a proprietary black box. When developers have the actual code in hand, they can work with it just like any other project: they can extend it, add new features, and patch security vulnerabilities using their existing tools and processes. We prevent design drift by integrating the design source, Figma, from the very beginning. By starting with the design file and creating a direct lineage to the code, we ensure the initial vision and the final implementation never stray too far apart. It’s like combining chocolate and peanut butter; that tight coupling of design and development is what sets it apart and makes maintenance sustainable.

You’ve designed this system for teams with a mix of design and technical skills. Can you provide a step-by-step example of how a designer using Figma and a developer in an IDE would collaborate within your platform to take an idea from concept to a verified application?

Of course. We explicitly built this for teams, not just solo developers, because we know modern application development is a collaborative effort. Imagine a designer finalizes a new user dashboard in Figma. They would then submit that Figma file to our system, perhaps with a few natural language notes like, “Generate a three-column dashboard with filterable data grids.” The AI agent then performs the first pass, creating the intermediate WaveMaker markup. At this point, a developer can immediately review this lightweight markup. It’s a moment of verification where they can see the structure and logic and confirm it matches the requirements, without having to sift through thousands of lines of code. Once they give the green light, the deterministic engine generates the real, production-quality code, which the developer can then pull into their IDE to wire up APIs, add business logic, and continue building. It’s a seamless handoff that keeps both the design and tech sides of the house in perfect sync.

What is your forecast for agentic AI in enterprise application development?

I believe we’re just at the beginning of seeing what agentic AI can truly do in the enterprise. The future isn’t about AI replacing developers, but about creating sophisticated, automated systems that work under the hood to handle the repetitive, time-consuming tasks. We will see these agents become integral parts of hybrid environments, seamlessly connecting visual design studios with developers’ IDEs. The trend will move away from simple code copilots and toward more specialized AI agents that can understand complex business intent, manage the full application lifecycle, and perform automated work with precision and efficiency. The key will be standardization—creating systems that are reliable, cost-effective, and built for the long-term realities of enterprise software, not just for generating code once.