Our guest today is Vijay Raina, an expert in enterprise SaaS technology with a deep understanding of software design and architecture. He specializes in untangling the complex web of browser rendering, particularly the often-misunderstood world of CSS stacking contexts. Today, we’ll move beyond simple z-index fixes and explore the foundational principles that govern how elements layer on a webpage. We will discuss why a high z-index can fail, the unexpected ways properties like transform create stacking issues, and a systematic approach to debugging these visual puzzles. We’ll also cover the trade-offs between different solutions, from restructuring HTML to using framework-specific tools, and even look at how to create stacking contexts intentionally without causing problems.

Many developers are surprised when an element with z-index: 9999 appears underneath another element with a much lower z-index. Can you explain the core principle behind why this happens and walk me through a common scenario, like a trapped modal, to illustrate this behavior?

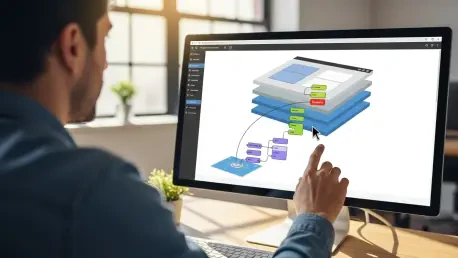

It’s a classic “gotcha” that catches even seasoned developers. The core principle, what I call “The Golden Rule” of stacking contexts, is that the browser doesn’t compare the z-index of every individual element on the page. Instead, it stacks the containers—the parent elements that have formed their own stacking contexts. Think of your webpage as a desk. The HTML elements are like pieces of paper. Some CSS properties, like position with a z-index, act like folders. Once you put a piece of paper inside a folder, its stacking order is only relevant inside that folder. A paper can never escape its folder to sit between papers in another folder.

A trapped modal is the perfect example. Let’s say you have a header with z-index: 1 and your main content area with z-index: 2. The modal, which is triggered from the header, is part of the header’s HTML. You give the modal an overlay with z-index: 9998 and the modal itself z-index: 9999. But when you open it, it’s stuck behind the main content. That’s because the browser first looks at the folders: it sees the .content “folder” with z-index: 2 and the .header “folder” with z-index: 1. It correctly places the content on top. The modal’s massive z-index of 9999 is completely irrelevant outside of its parent header’s context. It’s trapped.

Certain CSS properties like transform and opacity create stacking contexts, often unexpectedly. What is the browser doing under the hood that causes this, and how does this behavior relate to performance optimization? Please provide a specific example where this side effect could cause a layout issue.

This happens because of how browsers optimize rendering, not because of a direct visual instruction. When you apply properties like transform, opacity, filter, or perspective, you’re signaling to the browser that this element might be animated or changed frequently. To handle this efficiently, the browser promotes that element and its contents to a new rendering layer, sometimes called a compositor layer. Think of it as the browser taking that part of the page and saying, “I’ll handle this separately so I don’t have to repaint the entire screen every time it moves.”

The side effect of this performance optimization is that to manage this new, independent layer, the browser must treat it as a single, flattened unit. This process automatically creates a new stacking context. A common layout issue I see is with hover effects on cards. Imagine a grid of cards, and on hover, a card scales up slightly using transform: scale(1.05). This card now has a new stacking context. If that card also contains a dropdown menu with a high z-index, that menu can suddenly get trapped and appear underneath the next card in the grid, which doesn’t have a transform and exists in the root stacking context. The developer is left scratching their head, wondering why their z-index isn’t working, when the culprit was a subtle, performance-related browser behavior.

Imagine a dropdown menu is appearing behind the main content of a page. Describe your step-by-step process for debugging this issue using browser developer tools. How do you systematically climb the DOM tree to identify the specific parent element that’s creating the problematic stacking context?

My process is methodical because the issue isn’t with the element you see; it’s an ancestor’s fault. First, I right-click the submerged dropdown menu and select “Inspect” to jump straight to it in the Elements panel. In the Styles pane, I verify it has the high z-index I expect, let’s say z-index: 100. This confirms the element itself is likely configured correctly.

Next, the real hunt begins. I start “climbing the DOM tree.” In the Elements panel, I click on the dropdown’s immediate parent. I scan its styles, looking for any property that creates a stacking context—position with a z-index, opacity less than 1, a transform, a filter, and so on. If that parent is clean, I move up to its parent, the grandparent, and repeat the process. I keep climbing, parent by parent, investigating the styles of each one. Eventually, you’ll find the culprit. For a dropdown, it’s often a .navbar element with position: relative and z-index: 1. Then you realize its sibling, the .content container, has z-index: 2, and the whole picture becomes clear. The browser is correctly stacking the sibling containers, trapping your dropdown in the lower one.

When fixing a stacking context issue, you have several options. What are the key differences between changing the HTML structure, adjusting the parent’s CSS, and using a framework Portal? Could you explain the trade-offs of each and when you would choose one solution over another?

Each approach has its place, and the best choice depends on the component’s role and your codebase. The purest, and often best, solution is changing the HTML structure. For something like a global modal, you can simply move its markup out of the trapping parent and place it as a direct child of the . The trade-off is that this can complicate component logic, as the element is now physically detached from the component that controls its state. I choose this for truly independent UI elements.

Adjusting the parent’s CSS is more of a targeted fix. For our submerged dropdown example, we can’t move it out of the navbar. The solution is to find the parent .navbar and increase its z-index to be higher than its sibling .content container. This lifts the entire “folder” and its contents. The risk here is that you might start a z-index war, creating a new problem elsewhere. I use this when the element’s position is semantically tied to its parent.

Finally, Portals, available in frameworks like React and Vue, offer the best of both worlds. They let you render the component’s HTML anywhere—usually document.body—while keeping its logic and state connected to its original parent. This is a fantastic escape hatch for things like tooltips or dropdowns inside a container with overflow: hidden. You get the visual freedom of restructuring the HTML without the logical headache. It’s my go-to solution for complex components trapped by their parents’ styles.

Sometimes, the goal isn’t to escape a stacking context but to create one intentionally without side effects. How does the isolation: isolate property work, and in what practical situation would you use it to contain child elements, such as one with a negative z-index?

This is a fantastic, underutilized CSS feature. The isolation: isolate property is the cleanest way to create a stacking context. Unlike other methods that come with visual side effects—like opacity making things transparent or transform potentially blurring text—isolation does one thing and one thing only: it creates a new stacking context. It essentially puts a hard boundary around the element, saying “everything inside here sorts its layers relative to me, and nothing inside can ever appear behind me.”

A practical and common use case is containing a negative z-index. Imagine a card component with text. You want to add a decorative background shape using a pseudo-element that sits behind the text but on top of the card’s background color. If you just give the shape z-index: -1, it will dive to the bottom of the entire page’s stacking context, disappearing behind the card’s white background. By adding isolation: isolate to the parent .card element, you create a new context. Now, when the child shape has z-index: -1, it goes to the bottom of the card’s context, positioning it perfectly between the card’s background and its text content. It’s a simple, elegant solution without any unwanted side effects.

A tooltip with a high z-index is being clipped by its parent container. What specific CSS property is the most likely culprit for this trap, and why does it override the tooltip’s z-index? Explain how you would solve this, especially within a component-based framework like React or Vue.

The most likely culprit, nine times out of ten, is overflow: hidden on a parent container. This property is a special kind of trap because its job is literally to prevent child content from rendering outside its boundaries. A high z-index is meant to control stacking along the z-axis—how close something is to the viewer—but overflow: hidden controls the element’s clipping region in the 2D plane. The browser respects the overflow property first; it doesn’t matter how high the tooltip’s z-index is if its parent has been explicitly told not to let anything escape its visual box.

In a component-based framework like React or Vue, this is a perfect scenario for using a Portal. You can’t just remove overflow: hidden as it’s likely there for a valid layout reason. Restructuring the HTML manually can be a nightmare with dynamic components. So, you wrap the tooltip component in a Portal, which teleports its rendered HTML to the end of the document.body. The tooltip is now rendered outside the clipping container, completely free from the overflow: hidden trap. Meanwhile, its state and logic remain tied to the original trigger component, so it still behaves as if it were a direct child. It’s a clean escape that preserves both the layout and the component architecture.

What is your forecast for CSS layout and positioning?

I believe we’re moving towards a future of more intrinsic and logical layout systems, where CSS is less about micromanaging pixels and more about defining relationships and behaviors. Properties like isolation are a great example of this—a declarative way to solve a complex problem without side effects. I see this trend continuing with the evolution of Grid, Flexbox, and upcoming features like Container Queries, which allow components to adapt to their container’s size rather than the viewport’s. The focus will shift even further from absolute positioning and z-index battles towards creating robust, self-contained components that are resilient to their surroundings. The browser will handle more of the complex calculations, allowing us to build more complex and responsive user interfaces with simpler, more predictable CSS.