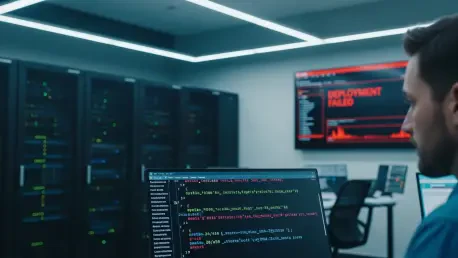

The familiar red dashboard and a sudden cascade of failure alerts send engineering teams scrambling, triggering a frantic search through recent commits and dependency trees for a bug that doesn’t exist. Hours are often consumed in this high-stakes hunt, with rollback plans being hastily drafted and code reviews scheduled, all under the assumption that a recent deployment has broken production. Then, a crucial but often delayed check of the Kubernetes cluster reveals the truth: the pods are running perfectly, serving traffic, and executing their functions exactly as intended. The code was never the problem; the deployment was, in fact, a success. This recurring disconnect between the status reported by deployment platforms and the actual state of a Kubernetes cluster is a significant source of wasted effort, leading to unnecessary escalations and a gradual erosion of trust in the very tools designed to streamline operations. Understanding the root cause of these false failures—the inherent timing gap between a platform’s rigid checks and Kubernetes’s model of eventual consistency—is essential for any team aiming to build resilient, efficient systems. By learning how to directly query the cluster for the ground truth, developers can bypass the noise of false alarms and focus their energy on solving real problems.

1. The Discrepancy Between Platform Reports and Cluster Reality

At the heart of many false alarms lies the fundamental difference in how deployment platforms and Kubernetes perceive time and state. Platforms are designed to provide definitive, near-instantaneous verdicts on deployment outcomes, often relying on fixed timeouts and periodic status checks to declare success or failure. Kubernetes, however, operates on a principle of eventual consistency; it is a declarative system that continuously works to reconcile the desired state with the current state. This process is not instantaneous and involves a series of asynchronous stages. A typical deployment begins with the image build phase, where source code is packaged into a container image. In many modern MLOps and serverless environments, this is handled by tools like Kaniko, which runs as a Kubernetes job directly within the cluster. Once the image is built and pushed to a registry, the pod scheduling phase commences. Here, the Kubernetes scheduler evaluates numerous constraints—such as resource requests, node affinity rules, taints, and tolerations—to find a suitable node for the new pod. Following successful scheduling, the container runtime starts, initiating the application, loading configurations, and preparing to serve traffic. Finally, Kubernetes uses health probes, such as liveness and readiness checks, to verify that the application is not only running but also capable of handling requests. This multi-stage, self-healing process can take time, and a platform’s premature status check can easily misinterpret a temporary delay as a catastrophic failure.

The timing problem is a primary source of this confusion. For instance, a deployment platform might be configured with a 60-second timeout for the image build stage. If its status check at that one-minute mark encounters a transient network error or finds the Kaniko build job is still compiling dependencies, it may immediately report a “Build Failed” status. Meanwhile, in the background, the Kaniko job continues its work unimpeded. At the 90-second mark, it might successfully complete the build and push the final image to the container registry. Shortly after, at the 100-second mark, the new pod could be successfully scheduled and deployed. By the 110-second mark, the application could be fully initialized and actively serving production traffic. From the perspective of the Kubernetes cluster, the deployment was a complete success. However, from the perspective of the engineers looking at the platform dashboard, the deployment failed nearly two minutes ago. This scenario highlights a critical insight: the platform’s status is merely a snapshot in time, not the definitive truth. The image may have been built, the pod may be running, and the service may be healthy, all while the platform’s user interface displays a persistent red error state. This gap between perception and reality makes direct cluster verification an indispensable skill for accurate troubleshooting.

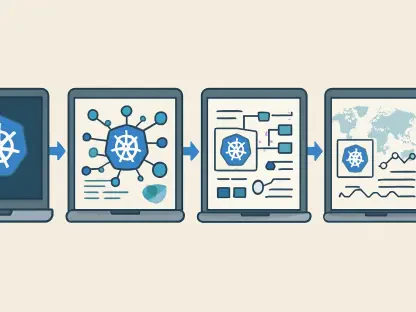

2. A Step-by-Step Verification Protocol

When a platform reports a build failure, the immediate instinct to debug the code should be resisted. The first and most critical question is not “What is wrong with the code?” but rather, “Did the build actually fail?” Answering this requires directly inspecting the Kubernetes cluster. The verification process begins by locating the Kaniko build pod, as it holds the definitive record of the image creation process. Since Kaniko runs as a Kubernetes job, it can be found using commands that list pods or jobs within the relevant namespace, often filtering for names containing “kaniko” or “build.” Once the specific Kaniko pod is identified, the next step is to examine its logs. The logs provide a detailed account of the build process, but the most crucial piece of information is the confirmation that the image was successfully pushed to a registry. A successful build log will contain a line such as Pushed registry.example.com/myapp/function@sha256:a1b2c3d4e5f6789.... This image digest—the unique SHA-256 hash—is the source of truth. Its presence confirms that the build job completed successfully, regardless of any contradictory status reported by the platform UI. Conversely, if the logs show errors or if this “Pushed” line and its associated digest are absent, it indicates a genuine build failure, and the investigation can then rightly shift to the application code, dependencies, or Dockerfile.

With the build success confirmed by the presence of an image digest, the investigation shifts to the deployment status of the application itself. The first step is to locate the running pods for the function or service in question using kubectl get pods. The Status column in the output provides an immediate overview: Running indicates normal execution, while statuses like Pending, CrashLoopBackOff, or ImagePullBackOff signal potential scheduling or runtime issues. If pods are in a Running state, the next crucial step is to confirm they are using the newly built image. This is achieved by extracting the imageID from one of the running pods. This ID contains the digest of the image the container is currently executing. The final step is a simple comparison: if the digest obtained from the running pod’s imageID matches the digest found in the Kaniko build logs, the deployment was an unequivocal success. The platform’s failure alert is a false alarm and can be safely disregarded. If the digests differ, it means the pod is running an older version of the image, and a manual rollout restart may be necessary to force Kubernetes to pull the correct version. If no running pods are found despite a successful build, the issue is not with the code or the image but with the pod scheduling process, which requires a different diagnostic approach focused on Kubernetes events.

3. Interpreting Kubernetes Events and Scheduling Failures

When a build is successful but the corresponding pod fails to enter a Running state, the Kubernetes event log becomes the primary tool for diagnosis. The kubectl describe pod command provides a wealth of information about a pod’s lifecycle, with the Events section at the end being particularly insightful. This section offers a chronological record of the scheduler’s attempts to place the pod and any issues it encountered. It is common to see a series of FailedScheduling warnings followed by a Scheduled event. This pattern often indicates a temporary resource shortage that the cluster’s autoscaler resolved by adding a new node. A platform with a short timeout might observe only the initial failures and report a permanent error, even though the pod was successfully scheduled just minutes later. This demonstrates how events provide the necessary context to distinguish between a transient, self-correcting delay and a persistent infrastructure problem. Understanding these events is key to recognizing that most scheduling issues are related to infrastructure, configuration, or resource constraints, not application code.

Several common scheduling error patterns appear frequently in production environments, and recognizing them can significantly accelerate debugging. An error message like “Insufficient memory” or “Insufficient cpu” is a clear signal that the cluster lacks the available resources to meet the pod’s requests. This is often a temporary condition resolved by the cluster autoscaler. “Node affinity mismatch” indicates that the pod’s scheduling rules, which dictate the types of nodes it can run on, do not match any available nodes in the cluster. Similarly, “Untolerated taints” means that while nodes with sufficient resources exist, they have been marked with taints (e.g., for GPU workloads or spot instances) that the pod is not configured to tolerate. A more severe issue is signaled by “FailedCreatePodSandBox,” which points to a network-level problem, such as an issue with the CNI plugin or IP address exhaustion, and typically requires intervention from the platform team. Finally, ImagePullBackOff indicates that Kubernetes cannot retrieve the container image from the registry due to reasons like an incorrect image name, missing credentials, or network connectivity problems. In almost all these cases, the problem lies within the cluster’s configuration or capacity, and the correct course of action involves adjusting resources or configuration, not modifying application code.

4. A Framework for Rapid Resolution

Developing a systematic framework for diagnosing deployment failures is essential for minimizing downtime and avoiding wasted effort. This framework should be based on a decision tree that quickly isolates the problem’s location and type. The first branch of this tree depends on the outcome of the Kaniko log inspection. If no image digest is found in the build logs, the problem is definitively located within the build process itself. This is a true code or configuration problem, and the appropriate action is to investigate the application’s source code, its dependencies, or the Dockerfile for errors. However, if a digest is present, the problem is not with the code. The next step is to check the pod’s status. If the digest exists, the pod is running, but the platform UI reports a failure, the diagnosis is a false alarm. The corrective action is to verify that the running pod’s image digest matches the one from the build logs and then close the alert. This scenario, one of the most common, requires no engineering intervention beyond simple verification.

The framework must also address situations where a successful build does not result in a running pod. If the Kaniko logs show a digest but no pods are running, the issue is almost certainly a scheduling problem within Kubernetes. The diagnostic path here leads directly to the pod’s events log, accessible via kubectl describe pod. Analyzing the events will reveal the specific reason for the scheduling failure, such as resource constraints or affinity rule mismatches, allowing for targeted adjustments to the cluster or pod configuration. Another possible outcome is a digest mismatch between the Kaniko build logs and the running pod. This indicates that the deployment is stale; Kubernetes is running an older, cached version of the image instead of the new one. The resolution for this is typically a forced redeployment using a command like kubectl rollout restart. Finally, certain errors, such as FailedCreatePodSandBox, point to deep-seated network or infrastructure issues. These problems are outside the scope of application developers to solve and should be immediately escalated to the platform or infrastructure team. By following this structured approach, teams can rapidly determine whether to fix code, adjust cluster resources, or escalate to the appropriate team, transforming chaotic debugging sessions into a methodical and efficient process.

Shifting Focus from Platform Alerts to Cluster Truth

Ultimately, the investigation confirmed that most deployment failures reported by platforms were not true failures but rather artifacts of a timing mismatch. They represented transient states captured before Kubernetes had the chance to complete its asynchronous, self-healing work. By learning to interpret Kubernetes events and directly verify cluster state, teams transformed confusing red dashboards into predictable, explainable system behaviors. This new approach eliminated countless hours of wasted debugging, reduced the frequency of unnecessary escalations, and fostered a deeper confidence in the underlying deployment systems. The key takeaway was clear: the next time a platform cried failure, the first step was to consult the cluster directly. More often than not, the pods were already running perfectly, simply waiting for someone to look past the dashboard and see the truth.