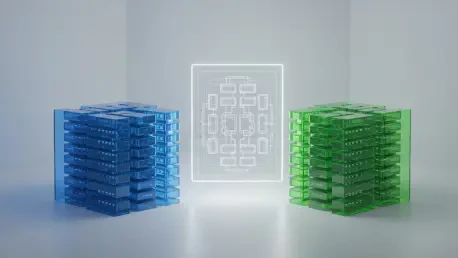

Many engineering teams adopt blue-green deployments as the gold standard for achieving zero-downtime releases in Kubernetes, believing they have sidestepped the inherent risks of standard rolling updates. This strategy, which involves running two identical production environments—one live (blue) and one idle (green)—allows for safe, isolated testing of a new release before directing live traffic to it. The switch is instantaneous, and rollback is as simple as redirecting traffic back to the original environment, making it a powerful tool for high-availability systems.

However, this safety comes with a hidden cost. The very nature of maintaining two parallel environments often leads to a subtle but critical failure mode: configuration drift. When deployments are managed manually or with simplistic scripting, the configuration for the blue environment can diverge from the green one over time. This discrepancy, often unnoticed until a critical release, undermines the core promise of the blue-green strategy. To combat this, a systematic, automated approach is required—one centered on a “Unified Manifest” pattern that ensures absolute consistency between environments.

Why Configuration Drift Is a Silent Saboteur

The root cause of configuration drift in blue-green deployments is the “Twin Manifest Trap.” In this common anti-pattern, teams maintain two distinct sets of Kubernetes manifest files, such as blue.yaml and green.yaml. When a configuration change is needed—for example, updating a database connection string or adjusting resource limits—a developer must remember to apply the change to both files. Human error is almost inevitable in this process; a change made in one file but forgotten in the other creates an immediate and often invisible discrepancy.

The business impact of this drift is tangible and costly. A deployment may succeed in the green environment only to fail catastrophically after the traffic switch because it relied on a configuration value that was never updated in the blue manifest. This leads to emergency rollbacks, frantic debugging sessions, and significant rework costs. According to research from Fujitsu on digital transformation projects, such synchronization errors were a primary cause of release failures, costing one project nearly 20 person-days of developer time annually just to resolve YAML misconfigurations.

Therefore, addressing drift is not merely a matter of encouraging developers to be more diligent. It is a systemic problem that requires an engineering solution. A systematic approach is essential to remove the possibility of human error and enforce configuration consistency by design. By treating the infrastructure as code, teams can build a reliable, repeatable process that guarantees both environments are, and always will be, identical in their shared configuration.

The Drift Free Blueprint A Three Part Solution

Strategy 1 Unify Manifests with a Single Source of Truth

The foundational step toward eliminating configuration drift is to abandon the practice of maintaining separate manifest files. The “Unified Manifest” pattern replaces this fragile system with a single, authoritative template that serves as the source of truth for both environments. Instead of hardcoding values specific to an environment, such as color: blue, the template uses variables like ${DEPLOY_COLOR}.

This approach shifts the responsibility of specifying the environment from the manifest file itself to the CI/CD pipeline. At deployment time, the pipeline injects the appropriate value—either “blue” or “green”—into the template before applying it to the cluster. Consequently, all other configuration parameters, from environment variables to resource requests, are guaranteed to be identical for both deployments because they originate from the same source file.

Real World Example Eliminating Configuration Mismatches

Consider a team that repeatedly experienced deployment failures due to mismatched database credentials between their blue.yaml and green.yaml files. By transitioning to a single deployment-template.yaml, they replaced hardcoded values with variables. Their CI/CD pipeline was then configured to render this template twice during a release, once with DEPLOY_COLOR=green for the new deployment and later with DEPLOY_COLOR=blue if a rollback was needed.

This simple yet powerful change completely eliminated an entire class of errors. The possibility of shared settings, such as DB_HOST or REDIS_CACHE_URL, differing between the two environments was reduced to zero. The team was no longer relying on manual diligence to maintain synchronization; the pipeline enforced it automatically, making their release process significantly more robust and predictable.

Strategy 2 Decouple the Build and Deploy Pipelines

A frequent anti-pattern observed in less mature CI/CD setups is the monolithic script that combines building a container image and deploying it to Kubernetes in a single, atomic step. This tightly coupled process is a major impediment to a true blue-green strategy. If the same script is run for both the green and blue deployments, it rebuilds the artifact each time, introducing the risk that the two builds are not binary-identical due to toolchain variations or last-minute code commits.

The best practice is to strictly separate these concerns into two distinct pipelines. The Continuous Integration (CI) pipeline’s sole responsibility is to produce a release artifact. It compiles the code, runs tests, builds a versioned container image, and pushes it to a registry. The Continuous Deployment (CD) pipeline then takes over, consuming this immutable, version-tagged artifact and managing its deployment to the various environments.

Real World Example Guaranteeing a Binary Identical Release

A financial services company struggled with intermittent failures where a new release worked perfectly in the green environment but failed under production load after the traffic switch. An investigation revealed that their unified build-and-deploy script was creating slightly different artifacts for each deployment. The build agent for the green deployment had a slightly different library version than the one that was later triggered for a hotfix, resulting in unpredictable behavior.

By decoupling their pipelines, they established a clear contract: the CI pipeline produces a tagged image (e.g., myapp:v1.2.5), which is then certified as a release candidate. The CD pipeline references this exact, immutable tag to deploy to the green environment for smoke testing. Once validated, the very same image tag is used for the production traffic switch. This ensured the code running in production was the exact same binary that had passed all previous quality gates, eliminating last-minute build variations as a source of failure.

Strategy 3 Automate the Traffic Switch and Cleanup

The final and most critical phase of a blue-green deployment—the traffic switch—is also the most susceptible to human error when performed manually. A series of kubectl patch or kubectl apply commands executed under the pressure of a release window can easily go wrong. A mistyped label selector or an incorrect service name can lead to an outage, defeating the purpose of the entire strategy.

To mitigate this risk, the switch-over and cleanup process must be fully automated. A reliable deployment pipeline should execute a well-defined, programmatic loop. This logic typically involves first identifying which color is currently live, then deploying the new version to the inactive color. After the new deployment is healthy and has passed automated smoke tests against its internal endpoint, the pipeline automatically updates the Kubernetes Service or Ingress to route live traffic to the new version. Finally, after a verification period, it safely decommissions the old resources.

Real World Example From 32 Manual Steps to a 5 Step Automated Pipeline

In the Fujitsu case study, the team’s initial blue-green release process was documented in a runbook with 32 manual steps, requiring an operator to copy and paste a series of commands. This process was not only slow but also fraught with risk. By implementing an automated release pipeline in Azure DevOps, they condensed this entire workflow into five high-level, automated stages.

The automated pipeline managed everything from identifying the current live color to running post-deployment validation tests and triggering the traffic switch by updating the service selector. The result was a dramatic improvement in both efficiency and reliability. The risk of human error during the critical switch was completely eliminated, and the team gained the confidence to deploy more frequently and with far less operational overhead.

Conclusion Paying the Management Tax on Blue Green Deployments

This exploration showed that while blue-green deployments introduce a “management tax” through increased operational complexity, this tax is entirely affordable when paid with automation and sound architectural patterns. The chronic issues of configuration drift, inconsistent artifacts, and manual release errors were not inherent flaws in the blue-green strategy itself but symptoms of an immature implementation.

The adoption of a Unified Manifest, decoupled pipelines, and an automated switch-over process was recommended for any organization struggling with the operational burden of managing parallel environments. These practices transformed the release process from a high-risk, manual chore into a reliable, programmatic workflow, directly addressing the root causes of deployment failures and rework costs.

Ultimately, the journey toward truly resilient, zero-downtime releases was achieved by adhering to three core principles. Teams succeeded by templatizing their manifests to enforce a single source of truth, decoupling the build from the deploy to guarantee artifact immutability, and automating the traffic switch logic to eliminate human error. This holistic approach provided the framework needed to unlock the full potential of blue-green deployments in Kubernetes.