In the dynamic world of cloud-native development, the line between building software and deploying it has become dangerously blurred, leading to fragile pipelines and release-day anxiety. We sat down with Vijay Raina, a leading expert in enterprise SaaS architecture, to dissect a powerful DevOps pattern that re-establishes this critical separation of concerns. Drawing from a successful implementation at Fujitsu’s Global Gateway Division, he reveals how a “Deployment as Code” strategy, centered on a flexible JSON configuration map and GitHub Actions, can slash release times and bring predictability back to Azure deployments.

Our conversation explores how to escape the “Config Matrix” hell that plagues so many projects, ensuring the binary that passes testing is the exact same one that runs in production. We dive into the practical mechanics of a configuration-driven workflow, the benefits of portable shell scripts over rigid plugins, and how this approach enables near-instant rollbacks. Finally, we’ll clarify the essential handoff between Infrastructure as Code and Deployment as Code, and look ahead to how these patterns are shaping the future of internal developer platforms.

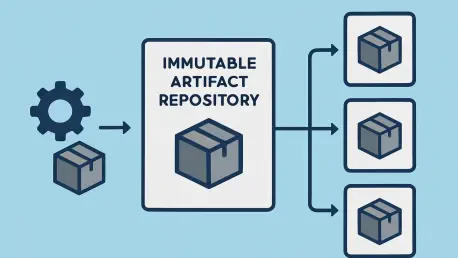

The article highlights “Artifact Drift” as a key problem. How does the “Build-Once, Deploy-Many” philosophy specifically prevent this, and what steps in your build and release phases guarantee the binary deployed to Production is identical to the one that passed testing?

This is the absolute core of the entire pattern. “Artifact Drift” is that nagging fear in the back of every engineer’s mind: is the code we’re pushing to production really the same code we just spent a week testing? The “Build-Once, Deploy-Many” philosophy attacks this directly by creating an unbreakable chain of custody for your code. First, our build phase compiles the code and packages it into a single, versioned .zip file. That’s it. No environment-specific variables, no transformations—just the pure, unadulterated application binary. Then, in the release phase, we upload this artifact to GitHub Releases and tag it with an immutable version, say v1.0.2. This artifact is now set in stone. From that point on, every single deployment—to Dev, Staging, or Production—pulls that exact same v1.0.2.zip file. The only thing that changes is the configuration we inject at the last possible moment. This guarantees, without a shadow of a doubt, that the code running in Production has passed through all the preceding quality gates.

You use a config.json file as the “Source of Truth” to escape the “Config Matrix” hell. Could you elaborate on how this centralized map handles complex logic, like targeting different deployment slots for dev versus prod, and how that ultimately simplifies the deployment workflow file?

The config.json is our Rosetta Stone for environments. It’s so much more than a simple key-value store. It’s a declarative map of our entire deployment landscape. The real magic is how it absorbs complexity that would otherwise pollute our pipeline YAML. For instance, in our setup, we often want our development environment deployments to go to a “staging” slot for smoke testing, while production deployments must go to the “production” slot. Instead of writing complex if/else conditions in the GitHub Actions workflow file, we simply define it in the JSON. The workflow’s only job is to say, “Deploy version v1.0.2 to the dev environment.” The config.json then tells our deployment script that for dev, the target slot is staging. This abstraction is incredibly powerful. The workflow YAML becomes clean, readable, and focused purely on orchestration, while all the messy, environment-specific logic is neatly organized and version-controlled right alongside our code.

Your pattern uses a portable shell script “operator” instead of relying solely on GitHub Actions plugins. Can you walk me through how this script parses the JSON map to execute the right Azure CLI commands, and explain why this portability is so critical for local testing?

Think of the shell script as our intelligent deployment agent. It’s the bridge between our declarative configuration and the imperative commands that Azure understands. The GitHub Actions workflow invokes this script, passing it just two things: the target environment name (e.g., prod) and the version tag of the artifact to deploy (e.g., v1.0.2). The script then uses a command-line JSON processor to read config.json, find the object corresponding to prod, and extract all the necessary values: the resource group name, the App Service name, the subscription ID, and the target deployment slot. With this information, it dynamically constructs and executes the precise az webapp deployment command. The portability this provides is a game-changer for developer velocity. I don’t have to push a commit and wait for a CI/CD runner to tell me I have a typo. I can run the exact same deployment command from my local machine against a dev environment, debug any issues in seconds, and have high confidence it will behave identically in the automated pipeline.

The Fujitsu case study mentions “instant rollbacks” as a major benefit. Could you detail the step-by-step process for rolling back a deployment using a previous version tag from GitHub Releases, and explain why this is safer and faster than rebuilding an old commit?

This is where the business value really shines. Let’s say we just deployed v1.0.2 and monitoring alerts start firing. The old way involved a frantic search for the last known-good commit, triggering a full rebuild of that old code, and hoping the build environment hasn’t changed in a way that creates a new problem. It’s slow, stressful, and fraught with risk. With our pattern, the process is calm and controlled. We simply go to the GitHub Actions deployment workflow, which is configured for manual triggers. We initiate a new run, but when it prompts for the version tag, instead of entering the latest, we type in the previous stable tag, v1.0.1. The workflow kicks off, pulls the known-good v1.0.1 artifact directly from GitHub Releases, and deploys it. That’s it. We’re not rebuilding anything; we’re just redeploying a trusted, immutable package. This turns a multi-hour panic-driven event into a predictable, sub-30-minute procedure, which is a massive win for operational stability.

You draw a clear line between Infrastructure as Code (IaC) with Bicep and this “Deployment as Code” pattern. In a real-world project, how do these two practices hand off to each other? At what point does the IaC pipeline finish and this deployment workflow take over?

It’s a clear and essential handoff, like a relay race. Infrastructure as Code, using tools like Bicep or Terraform, has one job: to provision and configure the “empty” Azure resources. Its pipeline runs and creates the App Service, the Cosmos DB account, the Function App—it essentially builds the stage. Once that IaC pipeline successfully completes and confirms that all the infrastructure is in place and correctly configured (e.g., network rules are set, identities are assigned), its part in the race is over. That’s the baton pass. The “Deployment as Code” workflow, which we’ve been discussing, then takes over. It assumes the stage has been built correctly and its only responsibility is to deploy the application code—the “bits”—onto that stage. They are two distinct, sequential lifecycles. First, you build the house (IaC), then you move the furniture in (DaC).

What is your forecast for the evolution of “Deployment as Code” patterns like this, especially as more teams adopt platform engineering and build internal developer platforms?

I believe this pattern is a foundational element for the future of internal developer platforms. The core goal of platform engineering is to provide developers with paved roads, or “golden paths,” that abstract away the underlying complexity of the cloud. This configuration-driven approach is a perfect implementation of that idea. A central platform team can build and maintain the robust deploy.sh script and the standardized GitHub Actions workflow. Application teams then don’t need to be Azure CLI experts. They simply consume this platform capability by defining their services and environments in their own config.json file. It creates a beautiful contract: the platform team owns the “how” of deployment, while the application teams own the “what” (their code) and the “where” (their config map). This scales beautifully and empowers developers to deploy safely and independently, which is the ultimate promise of a successful developer platform.