Relying solely on top-line accuracy metrics for computer vision models can create a deceptive sense of confidence, masking critical flaws that only surface during real-world deployment. While a model may achieve a 99% accuracy score on a curated test set, this impressive number often conceals a fragile and biased system. This guide provides a practical, step-by-step framework for moving beyond simplistic metrics to uncover and address these hidden vulnerabilities. By implementing a suite of targeted tests for group fairness and shortcut learning, developers can build models that are not only accurate but also robust, equitable, and truly reliable.

Beyond Accuracy: Uncovering Why Your Model Is Right for the Wrong Reasons

The uncomfortable truth in machine learning is that high accuracy is not synonymous with high performance. A model can achieve excellent scores on standard benchmarks while harboring fundamental flaws in its reasoning process. These systems are highly effective at finding the path of least resistance to minimize their training objective, a path that often involves exploiting spurious correlations and unintended patterns within the training data. This phenomenon, known as shortcut learning, leads to models that appear to function correctly but fail catastrophically when presented with even minor variations from their training environment.

A common discovery during rigorous model auditing illustrates this danger perfectly. For instance, a system seemingly proficient at identifying a specific animal may, in reality, be recognizing its typical background, such as grass for a cow or snow for a polar bear. The model latches onto these contextual cues because they are statistically reliable within the dataset, even though they are conceptually irrelevant to the task of identifying the animal itself. This reliance on shortcuts creates a brittle system that is correct for the wrong reasons, a flaw that standard accuracy metrics will completely miss.

To diagnose these deep-seated issues, a more comprehensive evaluation strategy is required. This guide details a practical testing suite divided into two critical areas of analysis. The first is group fairness analysis, which measures performance disparities across distinct demographic or categorical subgroups to ensure equitable outcomes. The second is a collection of shortcut detection tests, including transform-based probes, background-only assessments, and image shuffling experiments, each designed to expose a model’s over-reliance on non-essential visual information.

This approach is designed as an actionable protocol, not a theoretical survey. The tests outlined are intended for immediate implementation within existing development and validation workflows. By systematically probing for both fairness gaps and shortcut dependencies, engineering teams can gain a much deeper understanding of their model’s behavior and build systems that are fundamentally more trustworthy.

The Aha! Moment: When Standard Metrics Fail to Tell the Whole Story

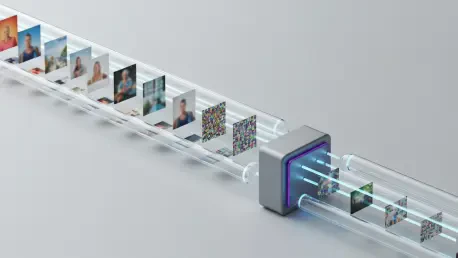

The limitations of conventional evaluation metrics become starkly apparent when a high-performing model is subjected to carefully designed stress tests. Consider a classifier that has achieved near-perfect accuracy on its validation set. When this same model is challenged with adversarially crafted inputs, such as images where the main object is heavily blurred, significantly cropped, or spatially rearranged through pixel shuffling, the results can be profoundly revealing. These manipulations are designed to degrade or remove the semantic information that a human would rely on.

The surprising discovery is often that the model’s accuracy remains stubbornly high, far exceeding what would be expected from random chance. A model might correctly classify an object even when its defining features are entirely obscured or when the image has been transformed into a mosaic of visual nonsense. This counterintuitive resilience is not a sign of sophisticated understanding; rather, it is a clear indicator that the model is not “seeing” the object in a human-like way at all.

This outcome leads to a critical realization: the model’s success is not rooted in a generalized understanding of the object’s form or function. Instead, it has memorized superficial patterns specific to the training dataset. These shortcuts can include consistent background textures, subtle camera artifacts, specific color palettes associated with a class, or other forms of dataset-specific noise. The model has learned to associate these incidental cues with the correct label, bypassing the more complex task of learning the object’s intrinsic properties.

This insight necessitates a fundamental shift in evaluation philosophy. A new framework emerges, moving beyond a single accuracy score to a dual-pronged approach that scrutinizes model behavior more holistically. This revised framework is split into two complementary lines of inquiry: evaluating group bias to ensure fairness across different subgroups and probing for shortcut bias to confirm the model relies on relevant, robust features rather than irrelevant context.

A Practical Test Suite for Exposing Model Flaws

Test 1: Measuring Group Bias for Subgroup Fairness

Group bias manifests when a model’s performance varies significantly across distinct subgroups within the data. This is a critical fairness concern, as it can lead to systems that systematically disadvantage certain populations. For example, a skin lesion classifier might be less accurate for individuals with darker skin tones due to their underrepresentation in the training data, or a quality control system on a manufacturing line could underperform on products from a specific factory due to variations in imaging equipment. The goal of measuring group bias is to identify and quantify these performance disparities.

The core requirement for conducting this type of analysis is an evaluation dataset that is richly annotated. In addition to the primary task labels (such as the object class), each data point must include metadata corresponding to the group attributes of interest. These attributes could be demographic factors like gender or ethnicity, technical parameters like the type of medical scanner used, or environmental conditions like lighting. Without this metadata, it is impossible to disaggregate the model’s performance and assess its fairness.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating Fairness Metrics

The process for calculating subgroup fairness metrics is methodical and straightforward. It begins by iterating through the annotated evaluation dataset, processing each image with the model to obtain a prediction. For each prediction, the associated group attribute is used to sort the result into a corresponding bucket. This allows for the separate accumulation of performance statistics for every defined subgroup.

Once all predictions are categorized, the next step is to calculate relevant performance metrics for each individual group. While accuracy is a common starting point, it is often beneficial to compute more nuanced metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score, as these can reveal different types of failure modes. The final output is a detailed fairness report that presents these metrics side-by-side for all subgroups, making it easy to spot significant performance gaps.

Establishing Your Fairness Thresholds

After generating a fairness report, the next step is to translate the raw numbers into a clear, actionable assessment. This is achieved by computing the performance gap, which is typically defined as the difference in performance between the best-performing subgroup and the worst-performing subgroup. For instance, if the model’s accuracy for one group is 95% and for another is 80%, the performance gap is a substantial 15 percentage points.

Quantifying the gap is only half the battle; the crucial subsequent step is to establish clear, predefined thresholds for what constitutes an acceptable level of variation. These thresholds should be set based on the application’s specific requirements and potential impact. A project might adopt a rule such as, “No subgroup’s accuracy shall be more than 5% below the best-performing subgroup.” This transforms the abstract concept of fairness into a concrete engineering constraint with a pass-fail outcome, forcing teams to address significant disparities before a model can be approved for deployment.

Test 2: Uncovering Shortcut Learning with Adversarial Probes

Shortcut tests serve a different but equally important purpose: they aim to understand why a model is succeeding. While group fairness tests reveal who a model might be failing, shortcut tests expose whether its successes are built on a solid foundation of learning or a fragile reliance on spurious cues. These tests function as adversarial probes, intentionally manipulating input images to break potential shortcuts and observe the model’s reaction.

These probes are generally categorized into three primary types, each designed to investigate a different kind of shortcut. Transform-based tests, such as applying heavy blur, disrupt the model’s reliance on fine-grained details. Background-only tests directly assess whether the model is using contextual information as a proxy for the object of interest. Finally, shuffling tests destroy spatial structure to determine if the model has simply memorized global statistics or noise patterns. Together, these tests provide a powerful diagnostic toolkit for uncovering a model’s hidden dependencies.

Transform-Based Tests: Does Your Model Depend on Fine Details?

One of the simplest yet most effective transform-based tests involves applying a heavy blur to the input images. This operation removes high-frequency information, such as sharp edges and intricate textures, which are often essential for defining an object’s structure. If a model’s performance remains high even after the object’s details have been smoothed into oblivion, it strongly suggests that the model is not relying on these features. Instead, it is likely using coarse, low-frequency information like color patterns and general shapes, which are often dominated by the image background.

This concept can be extended to a variety of other transformations to create a more comprehensive analysis. For example, by applying a Fourier transform, an image can be deconstructed into its frequency components. An analyst can then create test images that contain only low-frequency components or, conversely, have all high-frequency content zeroed out. Systematically removing different types of semantic information in this manner allows for a precise investigation into which visual signals the model deems most important for its predictions.

The Background-Only Test: Is the Main Object Even Necessary?

The “background patch test” is an exceptionally revealing experiment for diagnosing contextual shortcuts. The methodology is direct: from an image containing a known object, a small patch is cropped exclusively from the background, carefully avoiding any part of the primary object. This background patch is then placed onto a blank, neutral canvas and fed to the model for inference. The question being asked is simple: can the model identify the object when the object is not even present?

A high prediction accuracy on these background-only images is a major red flag and one of the clearest indicators of severe shortcut learning. It demonstrates that the model has learned a strong correlation between a particular background texture, color, or scene type and a specific object class. In essence, the model has determined that identifying the context is a sufficient and easier proxy for identifying the object itself. This type of learning is extremely brittle and is guaranteed to fail in novel environments.

The Shuffling Test: Is Your Model Just Memorizing Noise?

Another powerful probe involves destroying the spatial coherence of an image through shuffling. This can be done by dividing the image into a grid and randomly rearranging the grid cells, or by shuffling individual pixels. For a human observer, the resulting image is complete visual nonsense, as all structural relationships that define objects have been obliterated. The test is to see how the model responds to this chaotic input.

If the model’s classification accuracy on shuffled images remains significantly above the level of random chance, it points to a particularly problematic form of learning. This result suggests the model has not learned about objects or scenes but has instead memorized global statistical properties of the dataset. These properties, such as overall color distributions, common texture patterns, or even consistent sensor noise and compression artifacts, can persist even after the image’s structure is destroyed. The model is exploiting the dataset’s “style” rather than its semantic “content.”

Interpreting the Red Flags: What Your Test Results Mean

High accuracy on the background-only test is an unambiguous signal that your model is primarily using context to make its decisions. This result indicates that the training data contains strong, consistent correlations between object classes and their backgrounds. For example, if images of ships always feature water, the model may learn that “water” is the most predictive feature for the “ship” class. The model has found an efficient but incorrect shortcut, and its knowledge will not generalize to images of ships in drydocks or on land.

When a model maintains high accuracy on shuffled images, it reveals that it is exploiting global statistics or memorized noise patterns characteristic of the training set. It has learned to identify the unique “fingerprint” of the dataset itself, which might include specific color palettes, lighting conditions, or artifacts from a particular set of cameras. This type of learning is not robust because these superficial patterns are unlikely to be present in real-world data from different sources, leading to a sharp drop in performance upon deployment.

A minimal drop in accuracy on heavily blurred images demonstrates that the model considers backgrounds and low-frequency content more important than the object’s own edges and fine details. This suggests the model is making classifications based on broad color schemes or shapes rather than the specific structure of the object of interest. While this might work for datasets with distinct color-class correlations, it is not a generalizable strategy and indicates the model has failed to learn the truly defining features of the objects it is supposed to recognize.

From Diagnosis to Action: Fixing Biases at the Source

Identifying shortcut reliance and group bias should not be treated as a mere academic exercise but as the discovery of critical bugs in the system. Just like a software vulnerability, these flaws must be addressed at the source, which in machine learning primarily means a re-evaluation of the data and training procedures. Ignoring these issues is equivalent to shipping a product with known, significant defects that are guaranteed to cause failures for end-users.

The most effective mitigation strategies involve directly modifying the training data to eliminate the shortcuts the model has learned to exploit. This includes rebalancing datasets to ensure adequate representation for all subgroups, which helps to alleviate group bias. To combat contextual shortcuts, data curation efforts should focus on diversifying or randomizing backgrounds. For instance, if a model is using the background to identify an object, introducing new training examples of that object in a wide variety of unexpected settings will break that spurious correlation and force the model to learn the object’s intrinsic features.

Data augmentation provides another powerful set of tools for actively destroying shortcuts during the training process. Augmentations can be specifically chosen to target known vulnerabilities. Techniques like background swapping, where an object is digitally placed onto a random new background, explicitly make contextual information unreliable. Similarly, methods like cutout, which randomly erase parts of the image, encourage the model to build a more holistic understanding rather than focusing on a single, potentially spurious feature.

Ultimately, addressing bias and shortcuts requires adopting a rigorous engineering principle: if a model continues to rely on the wrong signals, it should not be shipped. This holds true regardless of how impressive its headline accuracy metric may appear on a standard validation set. A model that is not robust and equitable is not a finished product. This commitment to rigorous testing and remediation is essential for developing AI systems that are truly reliable and trustworthy in the real world.

Final Thoughts: Stop Trusting Accuracy Alone

The tests and principles outlined in this guide stemmed from the recognition that deep learning models are highly adept optimization systems. They will invariably find the easiest and most efficient path to a solution, a path that often involves exploiting subtle signals in the data that humans would dismiss as irrelevant, such as background textures, statistical noise, and other spurious correlations. This behavior is not a flaw in the algorithm but a natural consequence of its design.

The inherent risk of overlooking this behavior was the deployment of models that appeared successful on paper but were fundamentally brittle and unfair. Such models performed well on test data that mirrored the training set but failed unpredictably when faced with novel inputs or across different demographic subgroups. This created a significant gap between perceived performance and real-world reliability, eroding trust in the technology.

A more rigorous and skeptical testing methodology was therefore adopted. This involved moving beyond a single aggregate accuracy score and toward a more comprehensive evaluation framework. By combining per-subgroup fairness metrics with a suite of shortcut detection tests, it became possible to build a multi-dimensional profile of a model’s behavior, revealing both its strengths and its hidden dependencies.

This engineering-focused approach to fairness and robustness transformed an abstract concept into a concrete, testable, and solvable problem. The process of identifying, quantifying, and mitigating these hidden biases led to the development of models that were not just accurate on a benchmark but were demonstrably more reliable and equitable when deployed in complex, real-world environments.