The rapid proliferation of AI agents has created an urgent need for a standardized, secure communication framework, a challenge addressed by the late 2024 release of the Model Context Protocol (MCP). This emerging standard governs the interaction between AI agents and the services they use to perform complex tasks, enabling everything from desktop clients to fully autonomous LLM-based agents to seamlessly access and utilize external functionalities. By configuring an MCP server, developers can expose services to this new ecosystem, allowing agents to intelligently select the appropriate servers and features to fulfill user prompts. Functionally, an MCP server operates much like a traditional REST API, offering standardized remote access to resources, data, and services. This article provides a comprehensive guide on protecting these crucial gateways from unauthorized access, detailing the authentication and authorization mechanisms that underpin the MCP framework. It is designed for both the developers building MCP servers and the users integrating with them, offering a deep dive into the security layer that makes this powerful protocol viable. This discussion assumes a basic familiarity with MCP and focuses primarily on the November 25, 2025, specification while also referencing the widely implemented June 18, 2025, version to provide a complete picture of the protocol’s evolution. As the protocol continues to develop, it is essential to consult the latest specification to remain current with any changes.

1. Differentiating Between Local and Remote Transport Security

The foundation of MCP security is built upon the transport layer, where two primary technologies dictate the authentication and authorization approach: stdio and Streamable HTTP. The stdio transport is designed for “local” MCP servers, where the server operates as a local process directly initiated by the MCP client. In this model, all communication is routed through standard input and standard output, creating a tightly coupled relationship between the client and server. Because the MCP server is launched as a subprocess of the client, there is an inherent level of trust that eliminates the need for explicit authentication between the two components. It is analogous to piping a command to a local utility; the system implicitly authenticates the interaction. Configuration for the MCP server is typically managed through environment variables set by the client at startup. These variables can pass critical information, such as endpoint URLs for backend services. While no direct authentication occurs between the client and the server, the authorization process for downstream services still requires careful consideration. The MCP server can be provided with credentials, such as an API key, via these environment variables. The server then uses this key to authenticate its own requests to backend APIs, which in turn can enforce access controls based on the provided credentials. The specifics of this implementation vary depending on the MCP server, but the principle remains the same: authentication is delegated to the services behind the server.

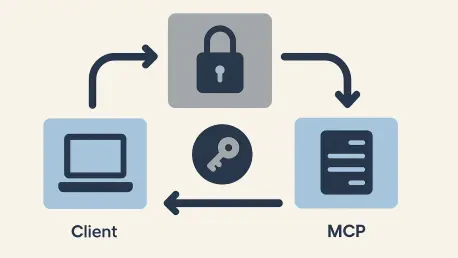

In contrast, the Streamable HTTP transport, introduced in the 2025-06-18 specification, is employed for “remote” MCP servers. A remote server can be hosted anywhere—on localhost, a private network, or a public URL—and is accessed over the network. This architecture necessitates a more robust and explicit security model, which is provided by the OAuth 2.1 protocol and other standards-based solutions. While some remote MCP servers, particularly those that are read-only and serve public data like documentation, may not require any authentication, they are the exception. Most MCP servers enable clients to perform actions, modify data, or access sensitive information, making authentication and authorization essential. In this scenario, the ecosystem is composed of three key actors defined by OAuth: the MCP client acts as an OAuth 2.1 client, the MCP server functions as an OAuth 2.1 resource server, and a separate authorization server manages the identity and access control process. The authorization server is responsible for authenticating the client, obtaining consent from the end-user for the requested actions, and issuing a secure token. The MCP client then presents this token to the MCP server, which validates it to confirm the client’s identity and permissions. Although the MCP specification designates this authorization process as an optional recommendation, it is strongly advised for any remote server implementation. It is also worth noting that an earlier transport, Server-Sent Events (SSE), was deprecated in the 2025-06-18 specification and has been superseded by Streamable HTTP for all new development.

2. Authenticating the MCP Server to Backend Services

Regardless of the transport protocol used between the client and the MCP server, a critical security consideration remains how the MCP server itself authenticates to the downstream services it relies upon to fulfill client requests. This aspect of the security chain is intentionally left outside the core MCP specification because the implementation logic is highly specific to each organization’s existing infrastructure and security policies. The most practical guidance is to leverage the same authentication and authorization solution that was already in place to protect the data, functionality, or service before the introduction of an MCP server. This approach ensures consistency and avoids introducing new, untested security models into a production environment. However, it is imperative to avoid treating the MCP server as a monolithic, fully trusted entity. The server is not acting on its own accord; it is an intermediary acting on behalf of the MCP client and, by extension, the end-user. This distinction must be preserved throughout the request lifecycle to maintain a granular and secure access control model. For instance, an MCP server handling a request originating from a client used by an administrator should possess elevated capabilities compared to one fielding a request from a standard user. This contextual information must be propagated down to the requests the MCP server makes to backend services, ensuring that the principle of least privilege is upheld.

To implement this delegation of identity in a standards-based manner, particularly when using the Streamable HTTP transport, Token Exchange is the recommended approach for environments where downstream resources expect OAuth tokens. In this flow, the MCP server receives the access token from the MCP client and presents it to an authorization server, along with information identifying the specific downstream resource it needs to access. The authorization server then validates the original token and mints a new, more specific token. This new token is carefully crafted to include claims about the original MCP client, the intermediary MCP server, and the target resource. This downstream token is then presented to the backend service, which can validate it and make a fine-grained authorization decision based on the complete chain of trust. This prevents the MCP server from having overly broad permissions and ensures that all actions are auditable back to the original user. While other proprietary solutions exist for managing this “on-behalf-of” flow, the MCP specification explicitly prohibits passing the original client token through to downstream services. This restriction is a crucial security measure to prevent token misuse and ensure that each component in the system only has access to the permissions it strictly requires. Therefore, choosing a robust mechanism like Token Exchange is not just a best practice but a necessity for building a secure and compliant MCP architecture.

3. Navigating the OAuth 2.1 Authorization Flow

For remote MCP servers, the authentication process is orchestrated through the OAuth 2.1 Authorization Code grant, a well-established standard for securing delegated access. The entire flow begins when an unauthenticated MCP client attempts to connect to an MCP server, but instead of granting access, the server responds with a 401 Unauthorized status. Crucially, this response includes a WWW-Authenticate header pointing to a metadata document hosted by the server. This metadata, defined by RFC 9728, contains a list of one or more authorization servers that the MCP server trusts to authenticate clients. This discovery step is the first link in the security chain, allowing the client to identify a valid path to authentication. Upon receiving this information, the MCP client selects an authorization server from the provided list—though in practice, having multiple options is rare and usually implemented for resiliency—and proceeds to fetch that server’s own metadata. This second metadata document, specified by RFC 8414 or OIDC Discovery, provides the client with all the necessary endpoints and configuration details for interaction, including the authorization endpoint for user login, the token endpoint for exchanging codes for tokens, and the methods supported for client registration. This structured discovery process ensures that the client can programmatically and securely navigate the authentication landscape without hardcoded configurations.

Once the MCP client has discovered the trusted authorization server, it may need to register itself to be recognized as a legitimate OAuth client. The specification provides several options for this, ordered by preference. The most secure method is out-of-band registration, where clients with an existing relationship with the authorization server are pre-configured. The next preferred method is Client ID Metadata documents (CIMD), an emerging IETF standard that allows a client to provide a URL pointing to its metadata. A more established but now secondary method is Dynamic Client Registration (DCR), which was the primary mechanism until a recent update to the specification. DCR allows a client to programmatically register by sending its details, such as its name and required redirect URIs, to a dedicated registration endpoint. The final option is to prompt the user to manually enter client information, which is the least desirable due to its poor user experience. It is critical to avoid sharing a single OAuth client ID across multiple MCP clients, as this would make it impossible to distinguish between them for logging, auditing, or security purposes and could lead to dangerous data leakage through cached credentials or scopes. After successful registration, the MCP client is prepared to initiate the Authorization Code grant, which is the core of the user-facing authentication process.

4. Executing the Authorization Grant and Token Validation

With registration complete, the MCP client initiates the OAuth 2.1 Authorization Code grant by directing the user to the authorization server’s authorization endpoint, which redirects them to a secure web page where they can log in and grant consent for the permissions, or “scopes,” that the client is requesting. The MCP specification, in alignment with OAuth 2.1, mandates several security enhancements over older OAuth 2.0 flows. Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE) is required and must use the strong S256 hashing method, which prevents authorization code interception attacks. Additionally, the request must include the resource parameter, as defined by RFC 8707, with its value set to the URL of the target MCP server. This ensures that the resulting access token is specifically “audienced” for that server and cannot be used elsewhere. Many MCP clients also request the ability to use the refresh token grant during this initial flow, enabling them to obtain new access tokens transparently without requiring the user to log in again after the initial token expires. At the conclusion of a successful authorization, the authorization server redirects the user back to the MCP client with an authorization code. The client then exchanges this code, along with its client credentials, at the token endpoint to receive a short-lived access token and, if requested, a long-lived refresh token.

Now equipped with a valid access token, the MCP client retries its initial request to the MCP server, this time including the token in the Authorization header with the Bearer scheme. Upon receiving this authenticated request, the MCP server has the critical responsibility of validating the access token. The exact validation steps depend on the token format and the authorization server, but for common formats like signed JSON Web Tokens (JWTs), a series of checks is required. The server must verify that the token’s signature is valid and was created by a trusted authorization server. It must also inspect the token’s claims, confirming that the audience claim matches the server’s own identifier, that the token has not expired, and that any other custom claims required by the server’s security policy are present. If the token fails any of these validation checks, the server must reject the request with a 401 Unauthorized status. Furthermore, even with a valid token, the server must check if the token contains the necessary scopes for the requested operation. If the scopes are insufficient, the 2025-11-25 specification introduces a process called “step-up authorization.” In this scenario, the MCP server responds with a 403 Forbidden status and a header detailing the additional scopes required. The MCP client can then initiate a new authorization flow to request these elevated permissions from the user, seamlessly escalating privileges when needed.

5. Best Practices for Token Management and Scopes

Securely managing the access token after it has been issued is primarily the responsibility of the MCP client. As a bearer token, an access token is akin to a physical key: anyone who possesses it can use it to access the associated resources. Therefore, it must be handled with extreme care. The client should store the token in a secure location appropriate for its environment, such as the operating system’s keychain for a desktop application or an encrypted store for a server-side agent. Under no circumstances should the token be transmitted as a URL query parameter or stored in insecure locations like logs or unencrypted files where it could be stolen. To mitigate the risk of a compromised token, access tokens should be configured with a short lifetime, typically measured in minutes or hours. To provide a seamless user experience despite these short lifetimes, MCP clients can request a refresh token during the initial authorization process. The refresh token must be stored with the same high level of security as the access token. When an access token expires, the client can present the refresh token to the authorization server to obtain a new access token without requiring the user to re-authenticate. This refresh mechanism can also be used preemptively before a token expires to ensure uninterrupted service. Additionally, the refresh grant offers a mechanism for privilege reduction; a client can request a new access token with fewer scopes than it originally held, effectively de-escalating its permissions when they are no longer needed.

Designing a clear and effective set of scopes is another critical aspect of securing a mobile content protocol (MCP) server. Scopes define the granular permissions that a client can request, and a well-designed scope strategy is essential for implementing the principle of least privilege. The process should begin with a thorough analysis of the functionality the MCP server will expose, involving consultation with both developers and potential end-users. The goal is to understand what users want to accomplish and to cordon off functionality based on its level of impact. For example, reading data is generally less destructive than writing it, which is less destructive than deleting it; these actions should correspond to different scopes. Functionality should be in a logical order, avoiding the creation of a single scope for every possible action, which can overwhelm users. Instead, create scopes that align with common use cases. Documentation is paramount; each scope must be clearly described so that users understand exactly what permissions they are granting. It is advisable to start with a minimal set of well-defined scopes and expand as needed while avoiding overly broad “super” scopes like “admin.” Finally, the security implications of the scope design should be reviewed with a security team. Unlike traditional APIs where client software can be difficult to update, MCP scopes are dynamically retrieved by the client from the server’s WWW-Authenticate header, allowing for more agile updates to the permission model.

6. Evolving Security Landscape and Future Directions

The security model for the Model Context Protocol has been a collaborative effort, shaped by input from a diverse range of organizations including model vendors, AI agent identity providers, and traditional identity management companies. This broad participation has resulted in a robust framework based on proven standards, but the protocol continues to evolve to address new challenges and use cases. One area not yet fully defined in the specification is the precise mechanism for how an MCP server should interact with its backend services, a gap that requires careful architectural planning by implementers. While the protocol wisely prohibits token passthrough, more standardized guidance around solutions like Token Exchange would benefit the ecosystem. Another challenge lies in the lifecycle management of dynamically registered clients; the RFC detailing how to manage or delete these clients is not yet widely supported, leaving an open question about cleaning up obsolete OAuth client configurations. Looking ahead, several draft specifications and proposals aim to enhance MCP’s authentication and authorization capabilities. The Client ID Metadata (CIMD) specification is gaining traction as a simpler alternative to Dynamic Client Registration, easing the client onboarding process by linking metadata to a URL.Fixed version:The security model for the Model Context Protocol has been a collaborative effort, shaped by input from a diverse range of organizations including model vendors, AI agent identity providers, and traditional identity management companies. This broad participation has resulted in a robust framework based on proven standards, but the protocol continues to evolve to address new challenges and use cases. One area not yet fully defined in the specification is the precise mechanism for how an MCP server should interact with its backend services, a gap that requires careful architectural planning by implementers. While the protocol wisely prohibits token passthrough, more standardized guidance around solutions like Token Exchange would benefit the ecosystem. Another challenge lies in the lifecycle management of dynamically registered clients; the RFC detailing how to manage or delete these clients is not yet widely supported, leaving an open question about cleaning up obsolete OAuth client configurations. Looking ahead, several draft specifications and proposals aim to enhance MCP’s authentication and authorization capabilities. The Client ID Metadata (CIMD) specification is gaining traction as a simpler alternative to Dynamic Client Registration, easing the client onboarding process by linking metadata to a URL.

Furthermore, discussions are ongoing to address more advanced authorization scenarios, and the community has considered integrating Rich Authorization Requests (RAR), a standard that allows for more fine-grained permission requests beyond simple scope strings, which would be beneficial for complex enterprise environments. The concept of generic extensions has also been proposed to allow for greater flexibility, with a draft extension for the OAuth client credentials grant already under consideration to better support server-to-server and automated agent interactions. Another promising draft extension aims to allow MCP clients to obtain tokens without the user-facing OAuth redirect, simplifying authentication in certain trusted enterprise scenarios. As these proposals mature, they will continue to refine the balance between security, flexibility, and interoperability. The protocol’s development is an open process, and community involvement has been instrumental in its success. The groundwork laid for securing MCP servers through a standards-based approach has provided a solid foundation for building a secure and interoperable AI agent ecosystem. The diligent application of these security principles has ensured that as AI’s reach expands, it does so responsibly and securely.